The three major PE strategies

6/5/20246 min read

OK, I realize that we have never covered the basics. So, if you already know the difference between VC, Growth, and PE, feel free to skip to the next post.

For those who are not yet completely comfortable with the jargon, here are some explanations:

Venture Capital (VC)

This is the most risky, yet arguably the most noble, form of investing in private companies! There are several sub-stages: An entrepreneur has a brilliant idea but is unsure if it will succeed. They seek seed (or “love”) money. Investors are willing to support such early stages if the idea appears promising. However, this is the riskiest investment stage. The market for the product may not even exist, and even if it does, numerous obstacles could prevent the product from ever reaching it. To cite a recent example: the French government, in one of its many communication campaigns (which rarely lead to action, unless you’re an overly optimistic entrepreneur), aimed to launch night trains. The only venture bold enough to attempt this eventually gave up. Why? It’s unclear if a market exists—though sleeping on trains could be an adventure. However, significant barriers exist, such as SNCF’s absolute refusal to allow alternative operators in France. Since SNCF is state-owned, no progress is made. Midnight Trains realized this and ceased operations, leaving its investors out in the cold.

At this stage, investment outcomes are binary: you either win or lose. And unfortunately, the losers far outnumber the winners.

Once a company survives the initial stage, it achieves “Proof of Concept (PoC).” There is a market, and the product is in demand. The company then begins its “series” funding rounds, ranging from Series A to E or F typically. These rounds provide the means to develop the product, enter the market, and scale, in anticipation of “essential” recognition: an IPO or sale to an industrial player.

How does this work? Why does a seed investor become wealthy as soon as a Series A or B round closes? The math is straightforward. At the “seed money” stage, small amounts are invested based on a modest valuation. Suppose business angels invest €250K based on a €2M valuation. They own 250 out of 2,250, i.e., 11.11%. If the company raises a Round A at a €20M pre-money valuation, a VC fund might contribute €2M. They would then own 2/22M€, i.e., 9.09%, diluting all existing investors. However, the angels who owned 11.11% before this deal effectively own 11.11% of €20M, i.e., €2.22M (from an initial €250K investment). Post-operation, their ownership percentage decreases, but the value of their investment increases significantly. This process continues through Series B, C, D, etc. If the company performs well, its valuation—and consequently, the value of all previous investments—increases. Keep in mind, they haven’t received any cash, but their investment’s value has been validated by another professional, providing some peace of mind.

Growth Investment

VC investment typically ends after a certain series, at which point it transitions to growth…

Securing a growth investor doesn’t necessarily indicate that the company is a sound investment. It merely shows that the company has progressed beyond a development stage and has earned its right to exist. Now, it needs to “scale” to become a leader, either continentally or globally. A successful VC investment usually demonstrates potential profitability (i.e., generating positive cash flows) on a small scale, having attracted enough customers to validate its product’s importance. A growth investment will likely incur losses in the first 2-3 years. A growth fund may opt to invest in a successful VC venture to expedite its global rollout. This requires substantial funding, as investments are needed for product adaptation to local markets and for building a sales force to market the promising product, albeit with a time lag. For instance, Salesforce, a leader in standard CRMs, had a solid product adopted across various industries in the US, but faced two challenges: (i) adapting to different end customers and (ii) expanding beyond the US. Numerous growth investors financed its losses before it became a reference point, went public, and turned into a profitable investment for many.

In summary, Growth Investment Funds assume less risk regarding product adoption but face considerable risks concerning product rollout, which demands significantly more capital.

To put it succinctly, both VC and Growth can enjoy substantial returns on capital in successful cases. However, they both entail considerable risks, with VC being riskier than growth. Growth investments have the option to scale back operations if deployment is premature, too rapid, or poorly managed. They are reassured by the fact that VC has already established the concept’s viability. VC, on the other hand, is truly pioneering in its investments…

Leveraged Buy-Outs (LBOs)

Subsequently, we have the buy-out segment, or “LBO,” which typically targets different companies.

An LBO involves acquiring an established and profitable business. There are various reasons why sellers might exit: retirement or death, the need for capital to invest in a new project they can’t self-finance, a desire to acquire foreign competitors without leaving their home market (thus seeking both capital and business support), or they might be a PE fund looking to realize a capital gain.

LBOs are often quite lucrative and can even generate profits from a mundane, slow-growing business because only a portion of the purchase price is paid upfront, with the remainder financed through debt.

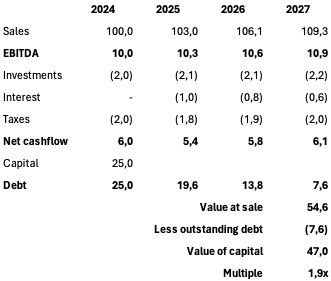

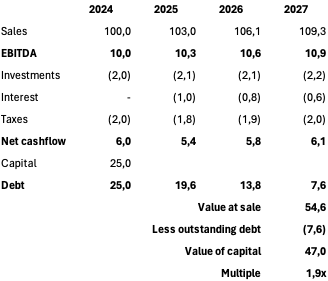

Consider a company acquired for €50M, or 5x its EBITDA, where the investor only contributes €25M. This company may not be growing rapidly (3% per year) and isn’t particularly profitable (10% EBITDA margin). As a result, it’s not highly valued (though multiples can range from 10x to 12x for attractive targets), but it generates sufficient cash to service the debt.

Several points to note:

The company doesn’t require significant investments due to its slow growth.

It’s profitable, hence it pays taxes. However, during the LBO, it will pay less in taxes because the interest on the acquisition debt (4% in this example) is tax-deductible.

Since it hasn’t demonstrated growth, it will likely be sold three years later at the same low multiple (5x). The buyer will deduct the outstanding debt from this valuation to determine the price payable to the current shareholders.

Actually, the investor sells the company only for 10% more than what he paid three years prior. This shows that even with modest growth but stable cash flow, an investor can achieve roughly a 2x multiple in just three years, equating to an annual return (or IRR) exceeding 23%!

What if the investor in this stable company acquires a similarly stable small competitor? Their returns would increase!

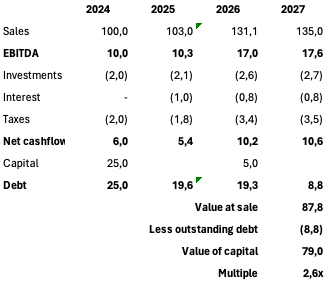

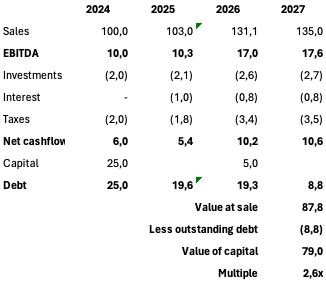

In the aforementioned example, we acquire a smaller yet slightly more profitable company at the same multiple in 2026 (with sales of €25M and a 12% EBITDA margin, i.e., €3M). We need to finance €15M. The bank is actually willing to increase its loan because the overall ratio of indebtedness remains stable.

Consequently, the investor needs to finance only €5M out of the €15M. Let’s assume that, thanks to synergies, we manage to increase the combined margin to 13% (a 1-point increase, which is not a significant change).

Then, we sell the company the following year, still at 5x EBITDA. We might even achieve a slight uplift, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. If we maintain the status quo, our investment multiple increases from 1.9x to 2.6x! This is attributable to the leverage and the marginal value creation.

Of course, there are numerous potential pitfalls in an LBO as well (which we might explore in a later post), but generally, this PE strategy is characterized by stable and recurring returns. Despite some write-offs in their portfolio, LBO funds can yield returns of as much as 2x-3x the initial capital (or more).

This return may be lower than that of VC or growth funds on individual deals, but it is associated with considerably less risk. This is why an investor dedicated to this asset class, who is also keen on mitigating risks, should ensure a well-diversified portfolio, both geographically and across these three strategies. We will delve deeper into this topic in the next post, where we will attempt to decipher the last posts concerning the matrix, the J-Curve, and the variations in returns.

We hope you found this article informative. Please share your feedback here, or contact us at contact@korafin.com!